For many farmers in Nigeria, climate change is no longer an abstract concept; it is a real and present threat disrupting their livelihoods and driving them into deeper debt and poverty, season after season.

By: David Arome

Mariam Aliyu was only 13 years old when she lost her parents to a fatal car accident in 2013. Being the first child of the family, she immediately took on farming in Mokwa LGA, Niger State, to cater to the rest of her siblings.

Mariam has shouldered this responsibility for 12 years, but recently, a climate-induced incident at her farm has left her with a crippling debt.

The Impact of Climate Change on Nigerian Farmers

When Mariam first took over her parents’ farm, she began with maize and yams; later, she added rice too. In all of that time, the rain never failed her; it came and left as it was supposed to.

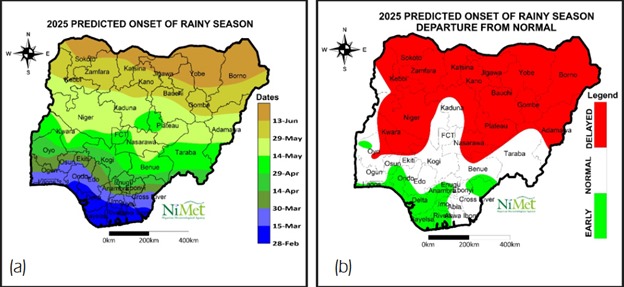

Recently, however, things have taken another turn: the rain has become erratic, making it impossible to predict and rendering the traditional knowledge that once guided planting and harvesting cycles ineffective. “Sometimes in 2024, the rain was delayed a little but was followed by flooding. I lost almost half of the rice,” Mariam recalls with tears.

While climate change is a threat to all, small-scale farmers who make up about 80% of Nigeria’s agricultural sector and account for 90% of its agricultural produce are disproportionately affected by its impacts.

It was a Wednesday which would have passed by like any other, except it didn’t, and the date now stays with her—May 28, 2025. It had rained the previous day, and Mokwa farmers, always excited at the sight of rain, were over the moon when the raindrops hit the ground. On Wednesday morning, Mariam began walking to the farm as she usually does. That day, she planned to plant some maize. On her way, she overheard some farmers saying the rain had caused flooding. Mariam quickly asked them to clarify, and when they did, she continued to her farm to see for herself. When she got there, she was met with a devastating sight; parts of her farmland were washed away. Heartbroken, she broke down in tears, remembering the debt hanging over her head.

How Climate Change is Fueling Debt Among Nigerian Farmers

Back in May 2022, Mariam took a loan of ₦1.5 million from a Microfinance Bank for the irrigation farming of vegetables; she had hoped to make a profit with which she could clear her piling bills and repay the loan within the space of two years.

But nothing went as Mariam had planned. Like in May 2025, heavy flooding had washed away parts of her farmland in Kudu, which led to a poor harvest. She could not make enough profit to pay off the loan; she went past the deadline, only being able to pay half of it, and then she renegotiated with the bank.

The losses do not just affect Mariam’s harvest but also her livelihood. For the past five years, the harvest has drastically dropped. Her hectares of farmland, where she gets 41 bags of maize and 1200 tubers of yam yearly, now hardly produce up to a 40% yield.

Climate change is a long-term change in weather patterns, such as rain, temperature, and sunlight, becoming unpredictable over many years, usually 10 or more. The Climate Risks Profile of Nigeria, 2021 report, reveals that the mean temperature until 2080 may rise between 1.8 and 3.9°C.

Over 80% of farmers in Nigeria depend on rain-fed agriculture, thus increasing their vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change. Nigeria is recognised to be vulnerable to climate change impacts, ranked 160 out of 181 countries in the 2020 Global Adaptation Initiative Index (ND-GAIN Index), which measures countries’ climate change vulnerability and readiness to adapt, helping prioritise resilience investments and policy action.

Climate Change and Its Devastating Effects on Nigeria’s Agriculture

Muhammed Maje

Like Mariam, many farmers in Niger’s Mokwa LGA have incurred losses due to the floods brought on by the erratic nature of the rains. Muhammed Maje, a farmer in Mokwa with nearly a decade’s experience, says that harvests have significantly dropped over the past five years. “Yearly, on average, I get 25 bags from maize, guinea corn, millet, and groundnut farms,” Maje said, explaining that the yield from last year’s farming dropped so much that he barely got 10 bags from all the crops he planted.

Crop yields in sub-Saharan Africa, including Nigeria, are predicted to drop by 22% by 2050 due to climate change as well as a projected population of 262.9 and 401.3 million in 2030 and 2050, respectively.

Maje attributed the poor yield to late rainfall, which delayed planting, and pest invasion, eating up the plants. Due to this shortfall, in 2024, Maje got a loan of ₦600,000 with an eight-month repayment plan from a Microfinance Bank to expand his farming. Like Mariam, he was also unable to meet his repayment deadline due to poor harvests. Left with no choice, Maje sold off his only motorcycle to clear the debt.

Now deep in a financial crisis, Maje’s only saving grace has been his wife, whom he set up in a grain-selling business during his bumper harvest years.

Rising Climate Change Risks Push Nigerian Farmers Into Poverty

Climate change has shifted the planting calendar, making it difficult for farmers to predict seasons, plan ahead, and harvest on time. “Most times, farmers are in a hurry to cultivate at the first drop of rain. Without having a second thought of the on-and-off pattern of the rain, which in turn affects the yield at the end,” highlighted Alhaji Shehu Kamaye, the State Youth Leader, All Farmers Association of Nigeria, Niger State chapter.

Mohammed Abubakar, a well-known farmer in the Ezhi community in Mokwa LGA, has also been a victim of the climate change crisis. Due to the erratic rainfall and repeated flooding, which have wiped out his crops over the years, he has been forced to replant twice, and this has, in turn, driven up his farming costs.

For nearly two decades, Abubakar has cultivated maize, pepper, guinea corn and groundnut. In that time, the past few years have been challenging, particularly 2025. “The flooding this year surpasses that of the previous years,” Abubakar recalled.

Beyond flooding, trees on his farmland that once provided shade for his pepper plants and boosted harvests have been cut down by intruders, stripping the crops of natural protection and reducing his harvest. These events have caused significant losses and a decline in his income.

Mitigating the Effects of Climate Change on Nigerian Agriculture

Waking up every morning with the thought of the losses, with family demands and increasing bills, throws him off balance. In 2024, he took a ₦1 million loan from Lapo Microfinance Bank to buy agrochemicals such as herbicides, fertilisers and other farming inputs to boost crop yield.

Like the others, Abubakar also had a hard time making a profit from the year’s farming, but against all odds, he was able to repay the loan five months past the deadline, drawing from his long-term savings and support from friends.

Reacting to the climate-induced losses of farmers, Zeenrent Zamani, Team Lead of the Murya Na Environmental Sustainability and Development Initiative, explains that the impacts of climate change would be easier on farmers across the country if the agricultural sector in Nigeria were enabling.

“Farmers are not protected with a financial ecosystem to thrive in catching up to climate variability,” Zamani said.

A Call for Action and Collaboration

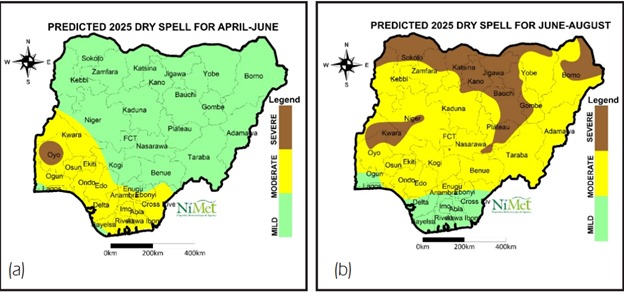

The Secretary and Head of Programs for the All-Farmers Association of Nigeria (AFAN) Niger State Chapter, Umar Dansabe explains that poor harvests were caused by the dry spells, characterised by the absence of rain, which altered the planting schedule and application of farming aids like fertiliser.

“Some crops cannot survive the dry spell, and those that survive do not produce the desired yield,” Dansabe noted.

The heat waves have incurred additional expenses on farmers, especially those in irrigation farming, the application of water to the soil to support plant growth. Farmers spend more on fuelling their generator to soften the hard ground. “The level of the dryness of the soil has increased the level of water application in their farms,” said Dansabe.

Unfortunately, the dry spells will continue to trouble farmers for a long time. A 2021 Climate Risk Profile on Nigeria shows that the water availability in the country is expected to decline by more than 75% from 3,300 m³ per capita, per year in 2000 to about 800 m³ by 2080, far below the United Nations 1,000 m³ per year threshold for water scarcity.

As the threat of dry spells and heavy flooding continues to loom, AFAN says it will work harder to ensure that more farmers are not put out of business as a result. One of the primary ways it does this is by advising farmers to insure their farms for emergency situations and offering them climate literacy training to better equip them on what they’re up against. In addition to this, the association has teamed up with the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, and the National Cereal Research Institute in Niger State to link farmers to improved drought resistance seeds. Although the improved seeds are expensive, the association is discussing with the Niger State government for a possible subsidisation of their prices. In addition to these efforts, Dansabe emphasises that “more financing, continued training and adherence to NiMET reports are important to enable farmers to scale through the hells of climate shocks.”

Climate Policy Implementation Gaps

Nigeria’s National Climate Change Policy (NCCP) is a guiding document that shows how the country plans to tackle climate change across all sectors, including the agricultural sector. It was updated in June 2021 and later backed by a strong law; the Climate Change Act was signed in November 2021 to ensure the policy is put into action.

Part of the policy emphasised targeted strategies such as smart climate agriculture and actions focused on the agriculture sector. It also recognises farmers’ vulnerability to climate change impacts like drought, flooding, shifting rainfall patterns, and soil degradation.

However, despite the vulnerability of farmers to climate threats, only seven out of Nigeria’s 36 states have adopted climate policy documents. Only Rivers and Ebonyi have further upgraded their policies to the Climate Change Act. Recently, Enugu State launched its climate change policy, climate action plan and climate education manual; the first completed subnational policy in Nigeria. “Every policy should be backed by law to give it legal footing for implementation,” Zamani emphasised.

The policy is a robust document that can help mitigate the glaring impacts of climate change. However, implementation remains the bottleneck in giving much traction to it.

“Having policies is not enough; there is a need to consistently review them in line with current trends, especially as climate change continues to reshape farming realities, risks, and resilience needs.” Dr Nwankwo Nnenna, a climate expert at the Federal Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology, noted. Most of the government policies exist on paper without implementation. The role of government goes beyond establishing policies but also enforcing them.

Conclusion: The Future of Nigerian Agriculture Hinges on Climate Action

Dr Chinwoke Clara Ifeanyi-Obi, a climate expert and senior lecturer from the Department of Agricultural Extension and Development Studies at the University of Port Harcourt, emphasises the need for access to information and collaboration among stakeholders to help farmers adapt to climate change.

“Research should be more evidence-based that policy makers can use as output in making policies that will favour farmers,” Dr Nnenna stated. By mainstreaming such research findings into policy and practice can provide practical solutions to the crisis faced by Nigerian farmers.

“Farmers’ lack of knowledge about climate change makes it challenging for them to adapt and repay loans. Equipping farmers with knowledge, technology, and support is vital for their survival. But if we build their capacity so that they are able to adapt their farming system to climate change, then with a little support, they will be able to upset those debts. They’ll begin to produce at a profit instead of running at a loss,” Dr Clara noted.

In boosting crop yield, Dr Nnenna calls for investment in the form of grants, improved seeds, irrigation farming, and smart climate agriculture—innovations that empower farmers to grow more and thrive despite climate shocks.

“The plight of these farmers is real, and the need for support, education, and adaptation is urgent. The future of Nigerian agriculture hinges on the ability to address the challenges posed by climate change and ensure that farmers can thrive in the face of uncertainty,” Dr Clara added.

Without urgent, sustained investment and policy enforcement, smallholder farmers like Mariam may lose more than just their crops—they risk losing their future. Nigeria must act now.

Credit Statement: This reporting was completed with the support of the Centre for Communication and Social Impact